Weight loss is a reduction in body mass achieved through dietary changes, increased physical activity, or medical interventions, characterized by a lower Body Mass Index (BMI) and decreased mechanical stress on weight‑bearing joints. When excess weight is trimmed, the load that the knees, hips, and spine have to bear drops dramatically, which can translate into less pain for people living with osteoarthritis-a progressive degeneration of articular cartilage and sub‑chondral bone. This article walks through the biology, the numbers, and the real‑world steps you can take to turn the scales in your favor.

Why Body Weight Matters for Joint Health

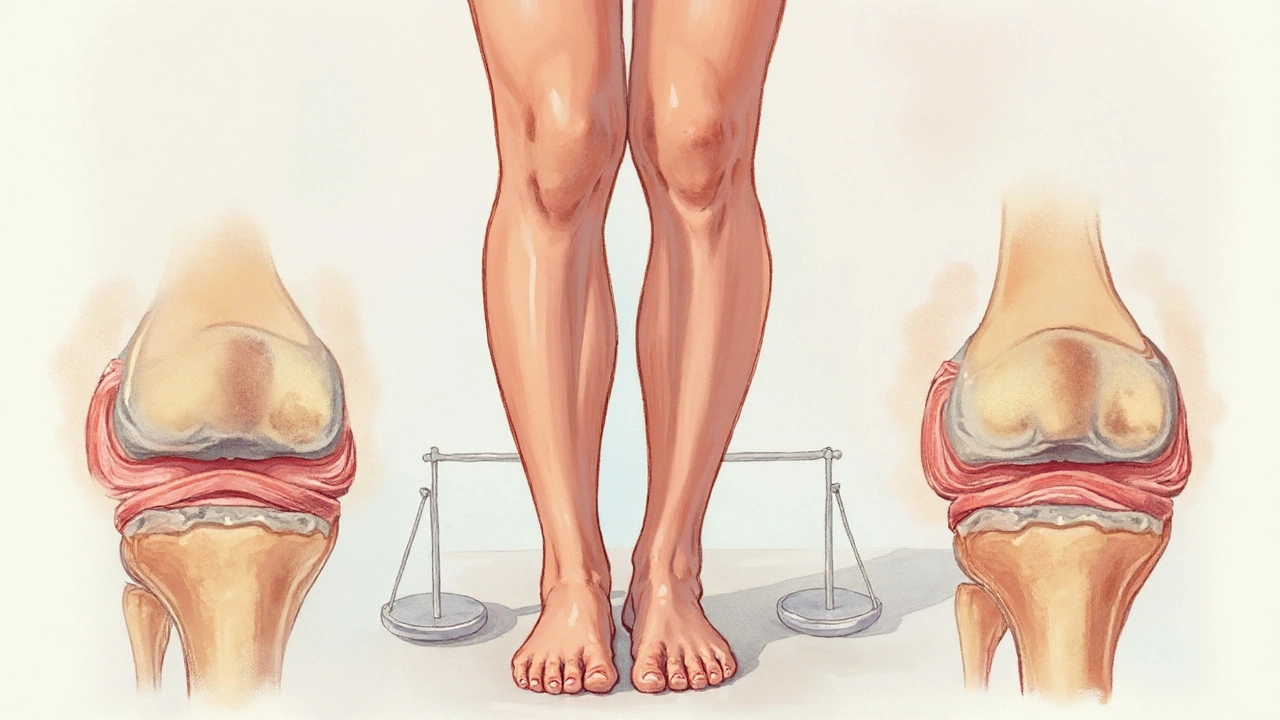

Every step you take transmits a force through your joints. For a person of average weight (≈70kg), each step can generate up to three times that weight in pressure on the knee. Add extra kilos and that pressure spikes exponentially. Researchers at the University of Sydney found that a 10% rise in BMI increases knee‑joint load by about 30%.

Two major pathways link weight to osteoarthritis progression:

- Mechanical overload: Heavier bodies compress cartilage, accelerating micro‑tears and reducing its ability to absorb shock.

- Metabolic inflammation: Adipose tissue secretes cytokines such as interleukin‑6 and C‑reactive protein, which fuel low‑grade inflammation that degrades cartilage from the inside.

Both routes converge on the same outcome-more pain, less mobility, and faster disease progression.

What the Numbers Say: Weight Loss and Symptom Relief

Clinical trials provide a clear picture:

- A 2008 randomized trial of 120 overweight knee‑OA patients showed that a 5% loss in body weight cut pain scores (WOMAC) by 20% after six months.

- The Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) cohort analysis (≈4,000 participants) reported that a 10% reduction in BMI slowed joint‑space narrowing by 0.2mm per year-roughly half the rate seen in those who maintained weight.

- A 2022 meta‑analysis of 22 studies concluded that every kilogram lost corresponds to a 0.5% drop in self‑reported pain intensity.

In plain language: lose the weight of a 5‑kg bag of rice and you’ll notice a meaningful dip in daily ache.

How Different Weight‑Loss Strategies Impact Osteoarthritis

Not all weight‑loss methods are created equal when it comes to joint health. Below is a side‑by‑side look at the most common approaches.

| Method | Typical %Weight Loss (12mo) | Pain Reduction (WOMAC) | Risk / Side‑Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calorie‑Controlled Diet + Exercise | 5‑10% | 15‑25% | Low; adherence challenge |

| Very‑Low‑Calorie Meal Replacement | 10‑15% | 20‑30% | Nutrient monitoring needed |

| Bariatric Surgery (Sleeve Gastrectomy) | 25‑35% | 30‑45% | Surgical risk, vitamin deficiencies |

| Pharmacologic Appetite Suppressants | 3‑7% | 10‑15% | Potential cardiovascular side‑effects |

Even modest diet‑only results rival the pain‑relief seen after surgery, but the latter delivers a bigger bang if you’re severely obese and can tolerate the operation.

Integrating Physical Activity: Protecting the Joint While Shedding Pounds

Exercise does double duty-burning calories and strengthening the muscles that support joints. A 2021 systematic review highlighted that low‑impact activities (swimming, cycling, brisk walking) improve WOMAC scores by an extra 10% when paired with weight loss.

Key guidelines for OA patients:

- Start with 10‑15 minutes of gentle aerobic work, 3 times a week.

- Progress to 30‑45 minutes of moderate intensity, aiming for a perceived exertion of 4‑6/10.

- Include strength training for the quadriceps and hip abductors twice weekly; these muscles reduce knee joint load by up to 20% during gait.

Remember, the goal isn’t marathon training; it’s consistent movement that burns calories without over‑loading fragile cartilage.

Nutritional Factors That Boost Weight‑Loss Benefits for OA

Beyond calories, certain nutrients directly influence cartilage health:

- Omega‑3 fatty acids (found in oily fish, flaxseed) dampen inflammatory cytokines, lowering CRP levels.

- VitaminD supports sub‑chondral bone remodeling; deficiency is linked to faster OA progression.

- Collagen peptides have modest evidence for improving joint comfort, especially when paired with weight loss.

Integrating these foods into a calorie‑controlled plan creates a synergy: you lose weight while feeding the joint a protective diet.

When Weight Loss Alone Isn’t Enough: Adjunct Therapies

Some patients still experience moderate pain after a 5‑10% weight drop. In these cases, clinicians often add:

- Topical NSAIDs (e.g., diclofenac gel) for localized relief.

- Viscosupplementation (hyaluronic acid injections) to improve joint lubrication.

- Physical therapy modalities such as ultrasound or manual mobilization.

The combo approach respects the multifactorial nature of osteoarthritis-mechanical, inflammatory, and neuromuscular.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even with the best intentions, people stumble. Typical mistakes include:

- Rapid, crash‑dieting: Leads to muscle loss, which actually raises joint load per kilogram of body weight.

- Ignoring pain signals: Pushing through severe soreness can worsen cartilage damage.

- Skipping follow‑up: Without periodic BMI checks, weight regain sneaks back in.

Pro tip: aim for a steady 0.5‑1kg per week, monitor body composition, and schedule quarterly check‑ins with your physiotherapist or GP.

Connected Topics You May Want to Explore Next

Understanding weight loss’s role in osteoarthritis opens doors to other relevant areas:

- Joint replacement surgery - when weight management and conservative care aren’t enough.

- Metabolic syndrome - how insulin resistance intertwines with joint inflammation.

- Biomechanics of gait - tools like gait analysis that quantify joint load.

- Tele‑rehabilitation - digital platforms that guide home exercise safely.

Each of these subjects deepens the conversation about long‑term joint preservation.

Frequently Asked Questions

How much weight do I need to lose to feel a difference in knee pain?

Most studies show that a 5‑10% reduction in body weight (about 5‑10kg for a 100kg adult) yields a noticeable drop in pain scores within three to six months.

Is diet alone enough, or do I need exercise too?

Diet and exercise work best together. Diet cuts the calories; exercise preserves muscle mass and reduces joint load, delivering up to an extra 10% pain relief compared with diet alone.

Can bariatric surgery improve osteoarthritis outcomes?

Yes. Patients who undergo sleeve gastrectomy often lose 25‑35% of their excess weight, and long‑term follow‑up shows a 30‑45% reduction in pain and slower joint‑space loss. Surgery, however, carries operative risks and requires lifelong nutritional monitoring.

What role do anti‑inflammatory foods play?

Omega‑3‑rich fish, walnuts, and olive oil can lower systemic CRP by 10‑15%, which may modestly protect cartilage. They’re a useful complement but don’t replace the mechanical benefits of weight loss.

How quickly can I expect to see joint‑space improvements on X‑ray?

Radiographic changes are slow. Most patients notice stabilisation of joint‑space narrowing after 12‑24months of sustained weight loss, rather than a literal increase in space.

Shayne Tremblay

September 21, 2025 AT 23:43You've already made a huge win by learning how weight loss can ease OA pain – that knowledge is power!

Every pound you shed reduces the load on your knees and hips, meaning less grinding on the cartilage.

Remember to pair a smart calorie plan with low‑impact activities like swimming or cycling; they burn calories while protecting your joints.

Stay consistent, track your progress weekly, and celebrate even the small victories – they add up fast.

You've got this, and the joint relief you’re aiming for is totally within reach!

Stephen Richter

September 26, 2025 AT 23:43Implementing a modest caloric deficit while preserving lean mass is advisable.

Musa Bwanali

October 1, 2025 AT 23:43Listen, you’re not going to see results if you treat diet and exercise as optional – they’re twin engines that drive joint health.

Cut those empty calories, hit the gym with purpose, and your knees will thank you with less ache.

Focus on strengthening the quads and hip abductors; that’s the most effective way to lower joint load.

Stick to the plan, push hard, and watch the pain melt away.

Allison Sprague

October 6, 2025 AT 23:43The article, while earnest in tone, suffers from a cascade of oversimplifications that merit scrutiny. First, the claim that a 5 % weight reduction yields a 20 % drop in pain is presented without a clear citation to the original study methodology, which raises questions about the statistical robustness of the result. Moreover, the authors neglect to mention the confounding influence of concurrent physical therapy, a factor that can independently modulate WOMAC scores. The mechanistic explanation of “mechanical overload” is reduced to a cartoonish metaphor of “extra kilos = exponential pressure,” ignoring the nuanced biomechanics of joint moments and muscle co‑contraction patterns. Additionally, the discussion of metabolic inflammation glosses over the heterogeneity of adipokine profiles among patients, thereby presenting a monolithic view of cytokine activity. The table comparing weight‑loss modalities, while convenient, fails to disclose the variance in adherence rates, which is arguably the most decisive predictor of long‑term success. In the bariatric surgery row, the risk column is woefully understated, omitting the potential for micronutrient deficiencies that can exacerbate bone health. The recommendation to “start with 10‑15 minutes of gentle aerobic work” lacks a progression framework, leaving novices without a roadmap for safe escalation. The article also sidesteps the psychological barriers to sustainable weight loss, such as emotional eating, which are well‑documented in the literature. The concluding FAQ section repeats information already covered, offering no novel insight. While the tone is undeniably upbeat, the piece sacrifices depth for brevity, which may mislead readers into underestimating the complexity of osteoarthritis management. In short, the article is a well‑meaning primer that would benefit from tighter sourcing, balanced risk discussion, and a more nuanced appreciation of patient heterogeneity.

leo calzoni

October 11, 2025 AT 23:43Anyone who thinks a few salad meals will magically eradicate knee pain is deluding themselves; the physics of load demand genuine calorie restriction and disciplined movement. The data you ignore screams that without measurable fat loss the cartilage will continue its relentless erosion. Stop romanticizing “just eat healthy” and confront the brutal arithmetic of body mass versus joint stress.

KaCee Weber

October 16, 2025 AT 23:43🌟 Oh dear Leo, I totally get where you’re coming from, and I love your passion for cutting through the hype! 😄 At the same time, let’s remember that every individual’s journey is a mosaic of cultural food traditions, socioeconomic realities, and personal motivations. 🎨 While the physics are indeed unforgiving, we can still weave in flavorful, nutrient‑dense meals that honor heritage and keep the plate exciting. 🍲 Pairing those with community‑based low‑impact classes, like water aerobics or dance, can turn weight loss from a chore into a celebration. 🎉 So, yes, the math matters, but the love for food and movement can coexist – it’s all about balance, support, and a dash of optimism! ✨

jess belcher

October 21, 2025 AT 23:43Weight loss and joint health go hand in hand; a balanced diet plus regular activity is key.

Sriram K

October 26, 2025 AT 22:43Exactly, Jess. A sustainable plan starts with realistic calorie goals and incorporates strength work for the quads and hips, which directly unloads the knee during daily tasks. Monitoring progress each month helps keep the momentum and allows adjustments before any setbacks appear.

Deborah Summerfelt

October 31, 2025 AT 22:43Honestly, all these weight‑loss hype pieces ignore the fact that some folks just aren’t built for “pain‑free” joints no matter how skinny they get.

Maud Pauwels

November 5, 2025 AT 22:43Deborah you raise a point, but even minimal weight loss can reduce load and improve comfort for many.